All ideas are old ideas

05 Oct 2012 - Chris Granger

My last post generated some discussion on telling people more about the ideas that came before Light Table. In many ways we’ve been rediscovering the past and since that initial blog post months ago, we’ve learned a ton about the ideas that we’re trying to bring to the industry. In the talks I’ve done recently, I’ve mentioned a bit about all the innovations that happened over the past 40 or so years that simply never made it to the mainstream. These are ideas championed by the lisp machine, structured editors, and the amazing efforts in the tooling surrounding languages like Smalltalk. We are always building on the shoulders of giants and all ideas are old in some way. Let’s deconstruct some of the concepts behind Light Table and look at a few of the projects that inspire us from decades ago.

Execution everywhere

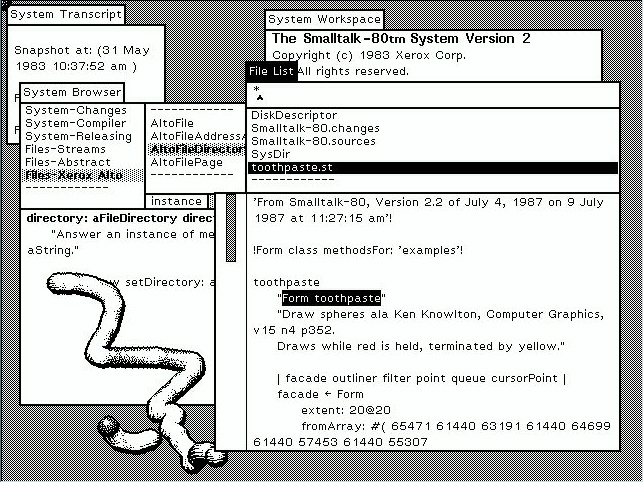

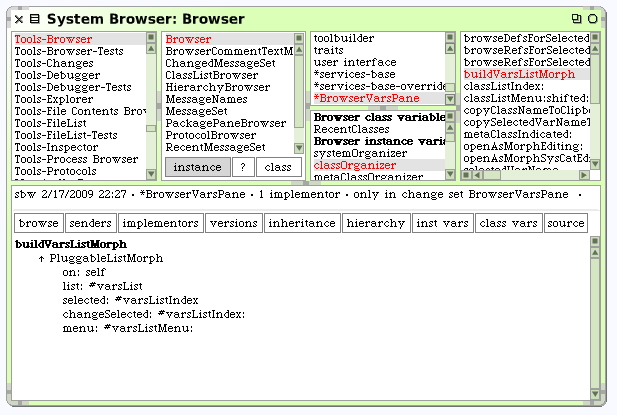

The notion of always having access to an execution environment is something that the smalltalkers and lispers have had for nearly 50 years now. The notion of developing in a REPL is as fundamental to Lisp as s-expressions and for good reason: it helps remove the disconnection we have with the software we’re building. These guys have always believed we should never have to go look somewhere to find out what something does; instead we can just ask the program and see what happens. Being able to simply try something, no matter how small, fundamentally changes the way you do work. You no longer write huge swaths of code at once and pray. Instead you write little bits and see if they work. Smalltalk environments like Squeak embraced this wholeheartedly - giving you “tiny” editors to put code in.

Instead of large editing surfaces, it provides you tools to navigate the code structure and explore information about the running program itself. When your tool is actually connected to the thing you’re building you can do far more interesting things than just provide a nice text editor. The smalltalkers I’ve talked to largely argue that editing is one of the least important parts of their workflow. Compared to those of us who swear by the amazing editors that are Vim and EMACS, that’s a pretty big departure. We all know, though, that most of our time isn’t really spent typing characters into a buffer. Having the ability to “talk” to our software can provide us far more valuable tools and far more efficient workflows.

A modifiable environment

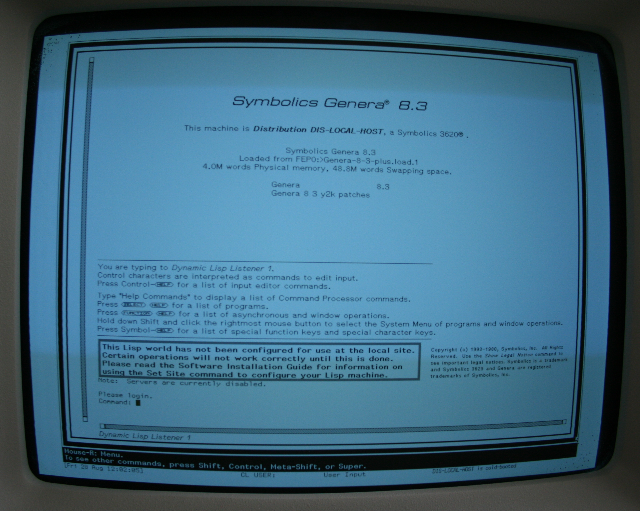

One of the great features of the lisp machine operating systems was the ability to re-evaluate whole parts of the OS at any time. It was a truly self-modifiable system. This meant that when something didn’t work exactly the way you wanted, you could just change it right there. All of our tools as developers should follow a similar pattern - we should be able to try something directly in the environment without jumping through a bunch of hoops.

The truth is that there really isn’t one workflow or interface to rule them all. Our projects and our personalities demand fluidity. The lisp machines and environments like Squeak gave us access to their internals and presented themselves as clay for us to shape without limitation. This level of freedom is something we have to carry with us in our efforts moving forward.

Editors with meaning

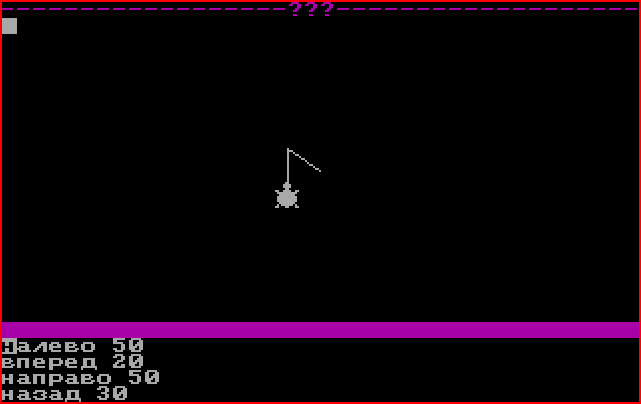

Logo took the abstract notion of programming a computer and gave it a concrete entity for people to latch onto: a turtle discovering a new world. This is a fantastic way to bring new programmers into the world of algorithmic thinking and many would argue that it is still one of the best teaching tools we have.

But what it does is far less important than how it does it. The power behind logo is in giving a visualization of what a program does and that visualization is what allows us to better understand what is happening. Bret Victor recently released a piece on Learnable Programming in which he says that until we are able to see our programs, we can’t really reason about them. While I wouldn’t go quite that far, it’s certainly true that we can’t reason about them well. Giving ourselves something concrete to interact with by bringing abstractions directly into our environment is, as I’ve said before, something I believe will make a fundamental difference in how we write software. Environments like HyperCard gave us concrete metaphors to work with and allowed us to reason about programs in a very meaningful way.

Old ideas finding a new home

People like Alan Kay set the ground work for an environment like Light Table to exist; they ushered innovation that fundamentally changed our profession. But the work doesn’t stop with what they did - so much more needs to be done and there’s a lot more to discover down these paths. These environments didn’t quite make it to the mainstream for reasons both intrinsic and historical, but the notions behind them help guide our efforts toward re-imagining the way we do work today. As such, Light Table is as much about rediscovering the past as it is about crafting a new future.